Exploring the Global Impact of Local Loss

Split the Village

A company of performers will gather in Lesotho, southern Africa in March and April 2016 to begin work on Memory of A Drowning Landscape, the next step in the creative work they began with Split the Village, a performance/installation project focused on the environmental destruction and cultural heritage loss of dam building. The company will include students from the National University of Lesotho’s Theatre Unit, facilitators from The Winter/Summer Institute (WSI) and members of the Theatre Association of Lesotho (THALE), in collaboration with the Morija Museum and Archives and villagers from the Morija community. We plan to create a collaborative theatre performance and installation piece for The Morija Festival of Arts and Culture that looks at climate change, cultural heritage and the erosion of “place” in Lesotho.

Visit the project on Make Art with Purpose

The Project

Split the Village is an ongoing experiment using performance and installation to capture the essence of place and begin to build a transitory cultural archive. The project’s inspiration is a 14 kilometer stretch of the Phuthiatšana River valley in rural Lesotho which was flooded in late 2014 when construction of the Metolong Dam was complete. Multidisciplinary and community motivated, the performance will revolve around the notion of “intangible cultural heritage” – the practices, representations, knowledge and skills that communities, groups and individuals recognize as part of their heritage.1 In the case of the Phuthiatšana, this includes stories, songs and dances associated with the river; sites of ritual and spiritual power in the river gorge; local knowledge of river plants and herbs; as well as the community’s visual map of the landscape itself, which was irrevocably transformed once the flooding began.

While Split the Village is not necessarily “about” the Phuthiatšana River and the Metolong Dam, the fated tract of river valley serves as the theatrical jumping off point for the piece. Starting with the call-and-response echo of river chasm conversations, the pattern of communally chiseled footpaths, and the tall tale of a runaway coffin – the short-term goal is to create a provocative performance experience that explores the global impact of local loss. The long-term goal is to create a global archive “for and of” place, a virtual “home” for memories, images, descriptions and aural evocations gathered from across the globe. The GlobalVillageArchive is still in-process, with an anticipated summer launch – more details available soon. Split the Village is also a partner project with MAP (Make Art with Purpose) – which will co-host our GlobalVillageArchive.

This short film, produced by Glynis Barber and Stever Teers, features Protimos' 'Community Legal Empowerment' Seinoli Project in Lesotho. The project works to obtain compensation for the thousands of people who have been adversely affected by the construction of the Lesotho Highlands Water Project.

History of Split the Village

The groundwork began in Lesotho in 2012 with preliminary research on dam relocations, contact with the archaeology team working on the Metolong sites (see below), and interaction with my theatre students and with cultural heritage, history and development studies colleagues at the National University, where I spent most of the year as a visiting Fulbright professor.

The idea of Split the Village, to generate an artistic response to the community and cultural destruction of dam building, benefited from the work of a team of archaeologists on site in Lesotho in the lead-up to construction of the dam. Since 2009, the core of the team from St. Hugh’s College, Oxford, UK2, led by Charles Arthur, has been a key part of the Metolong Cultural Resource Management Project, a large-scale heritage mitigation project funded by the World Bank, Metolong Authority and the Lesotho Department of Culture. The team worked closely with faculty and students from the National University of Lesotho, the Morija Museum and Archives, and community members along the Phuthiatšana, to document the rock art in the river gorge, unearth and assess archaeological deposits, and to carry out interviews and oral histories. The team’s work has been exceptional in many ways, particularly in its pursuit of community connection and participation. That involvement included a training program for young archaeologists within Lesotho, which resulted in the formation of The Lesotho Heritage Network founded by program graduates.

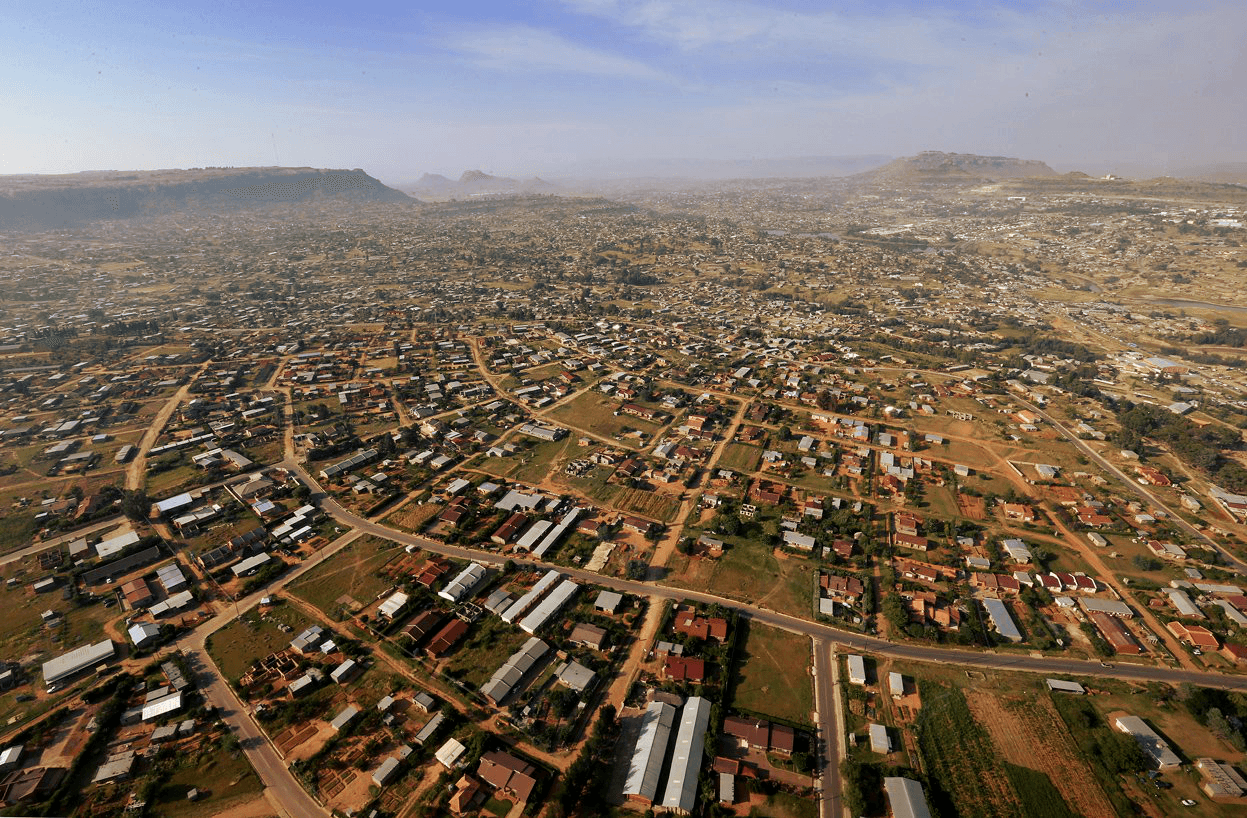

The Metolong isn’t the first dam to be built in Lesotho, a small mountainous country completely surrounded by South Africa, but it’s unique in two ways. First, unlike the huge Katse and Mohale dams (Phase I of the Lesotho Highlands Water Project) which siphon drought-ravaged Lesotho’s water off to Johannesburg and Pretoria, the smaller, localized Metolong is designed to bring water to the capital city, Maseru, and water and electricity to the area around the National University. Second, while it’s not the norm for about-to-be-inundated sites in Africa to be recorded or preserved, in the case of the Metolong there was an uncharacteristic pause in construction to allow the profusion of rock art and historical remains in the area to be catalogued, and so that efforts could be made to preserve the intangible cultural heritage of the area.

Wherever dams are built the ecological balance is disrupted along with people’s lives and culture. While the number of families facing relocation because of the Metolong was small, the cultural and environmental impact was significant. Lesotho has experienced decades of destruction, removals, relocations and cultural disarticulation as a result of the Katse and Mohale dams. The country faces more of the same with Phase II of the Highlands Water Project which began last year. Community-centered work like that carried out by the Metolong archaeology team, along with efforts like Split the Village to use visual and performance art to reflect the rich complexity of this small stretch of river valley, can transform how we see what is about to disappear, and might serve to reframe the discussion of how, where and if to build future dams.

1.) Convention for the Safeguarding of Intangible Cultural Heritage 2003, UNESCO

2.) Mitchell, Peter and Charles Arthur. Archaeological Fieldwork in the Metolong Dam Catchment, Lesotho, 2008-10. Nyame Akuma 74: 51-62